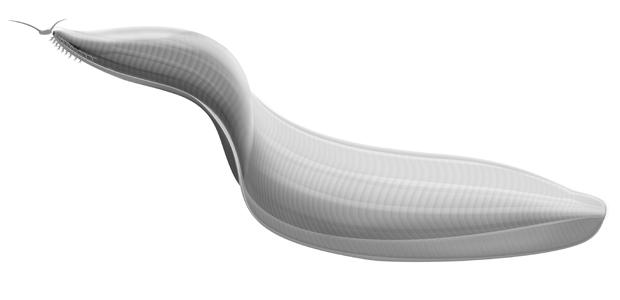

Researchers from Canada and the United Kingdom have described the most primative vertebrate – an eel-like creature from Yoho National Park.

Shake our ancestral tree hard enough and researchers from Canada and the United Kingdom say a half-billion year-old, eel-like creature from British Columbia’s Burgess Shale will fall out.

More than a hundred fossils of the creature – known as Pikaia Gracilens – have now been analyzed and researchers say it’s the most primitive of the chordates, which evolved into humans.

“When I first looked at Pikaia, I noticed an arrangement of segments, and in most invertebrates, like earthworms, these segments are effectively circular,” Simon Conway Morris, a Paleontologist at the University of Cambridge and the study’s lead author, told Science-Fare.com. “In Pikaia they have a sigmoidal, S-shape and that shape we suggest, is completely diagnostic of the group which includes the fish.”

“Of course this has been modified in all sorts of ways,” he added.

The researchers say Pikaia had about a hundred of these complex segments – known as myomeres. The zig-zag pattern, he says, is similar to the white lines that run through a piece of salmon.

“The internal anatomy of the musculature is really rather complex,” Conway Morris said. “We see just the same thing in Pikaia.”

What isn’t complex is Pikaia’s backbone. Using an electron microscope, researchers identified the precursor to our modern backbone – known as the notochord. It’s essentially a flexible pole that runs the organism’s body length to give it structure.

The technology’s even allowed them to identify primitive gill pores – but even Conway Morris admits that if they are, they’re very primitive.

“[They’re] openings just behind the mouth that allow seawater to enter the mouth and then to exit,” Conway Morris said. “They might be involved in respiration.”

Since it was first discovered in 1911, Pikaia gracilens has suffered a sort of identity disorder.

When it was first described by the Burgess Shale founder, Charles Doolittle Walcott, he placed it in line with the earthworms as an annelid – something pointed out to him in a letter from his colleague at Yale, Charles Schuchert that same year.

Then, when it was further described by Conway Morris – who first started studying the creature in the 70’s as part of his PhD – it was placed in the proper phyla as a chordate, but, he described another organ as the notochord.

Now, the researchers have identified the proper notochord, along with other features that make Pikaia our most simple ancestor, including a primitive nerve cord and vascular system.

They’ve even assigned a new name to the organ once believed to be the notochord – it’s now known as the dorsal organ – but that’s all they know about it.

They hypothesize it to be a relic from an even more primitive and obscure set of organisms, known as the yunnanozoans.

“The yunnanozoans have a rather remarkable segmented body, but it appears to be with a cuticular surface,” Conway Morris said. That fingernail-like surface, he says, is similar to what they see in the dorsal organ.

“One possibility is that it’s used for storing food material,” Conway Morris said. “The difficulty with the dorsal organ is, although it’s clearly preserved, you can’t see anything inside it.”

Also noticeably absent the researchers say, are eyes and a post-anal tail.

For Christine Janis, who’s a vertebrate paleontologist at Brown University – she’s also known on the internet as ‘PaleoBarbie’ – the combination of complex musculature and a terminal anus deserve more attention.

“It used to be thought that the original mobile portion of a chordate was its tail,” Janis, who’s the co-author of Vertbrate Life – a textbook on vertebrate biology – told Science-Fare.com.

Conventional thought was complex muscles came after and developed from the tail.

“If Pikaia really does have a gut that extends to the end of its body, well, then that clearly isn’t true,” Janis said.

It could be the reverse she says and complex musculature could have given rise to the tail.

Modern technology has added another set of tools to help shape our ancestral tree of life. Recent genetic analysis of two important organisms, the tunicates and amphioxus – the sea squirt and lancelet – forced researchers to rethink how all the puzzle pieces fit together.

“We had a story that was based on living forms and now some of those details are being called into question,” Janis said. “The molecular data is now quite clearly showing that tunicates are closer to vertebrates than amphioxus is.”

Pikaia doesn’t necessarily change the thought she says, but flows along with the new information – and is truly a representative from 500 million years ago. In fact, it was probably a living fossil a half-billion years ago.

It’s simple, primitive body plan doesn’t make it our oldest ancestor though, researchers say. By the time Pikaia landed on the scene during the Middle Cambrian – a period during the Cambrian explosion – recent research suggests vertebrates had already started to pop up.

The research was published in the latest issue of the British scientific Journal, Biological Reviews.

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded