An international team of researchers have found evidence that our hominin ancestors were making stone-tipped weapons for hunting approximately 500,000 years ago.

Stone points unearthed at a prehistoric watering hole in South Africa are telling a fascinating story about our hominin ancestors. Excavated from layers of soil that are approximately 500,000 years old, a team of researchers from Canada, South Africa and the United states found their makers used them as spear tips.

“Adding a stone tip to the end of a spear has a lot of advantages,” Jayne Wilkins, study co-author and PhD candidate in anthropology at the University of Toronto in Canada, told SciFare.com. “It causes more bleeding in the prey and essentially makes them die faster.”

“It’s like adding a sharp blade to the end of a spear,” she added.

The new discovery doesn’t just push the idea of manufacturing stone-tipped weapons back 200,000 years – an innovation in technology known as hafting – it places them into the hands of Homo heidelbergensis, the common ancestor of modern humans and Neandertals.

“What these points are telling us, is that our story as innovative and effective hunters began a very long time ago and the traits that make us the way we are, have been accumulating over a very long period of time,” Wilkins said.

The innovation in technology didn’t necessarily allow our ancestors to start inflicting carnage on larger prey – other research teams have found evidence that they were doing that more than 750,000 years ago. The researchers say it enabled them to hunt more effectively though.

“They can more reliably and regularly access meat,” Wilkins said. “That’s going to have a huge impact on their diet and other traits.”

Since H. heidelbergensis started walking into the fossil record roughly 600,000 years ago, during the middle Pleistocene, it doesn’t complicate things to associate this innovation in technology with them – both modern humans and Neandertals were using hafted tools, so it’s not a stretch to associate their creation with the common ancestor.

“Before this finding, there were no big behavioural changes represented in the record,” Wilkins said.

The fossil record for H. heidelbergensis certainly shows one though. Compared to Homo erectus – their immediate ancestor – H. heidelbergensis had a larger brain case and other researchers have linked that expansion to them getting regular access to high quality food.

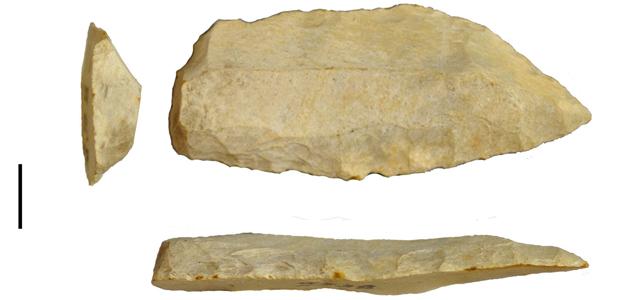

Modifications near the base of each spear tip hint at the challenges H. heidelbergensis really faced while making stone-tipped weapons – securing the individual components together – and materials like tree sap and sinew, hint at possible solutions.

“You have to prepare each material individually and then you have to combine them all into one,” Wilkins said. “It takes a lot more foreplanning than a single component tool.”

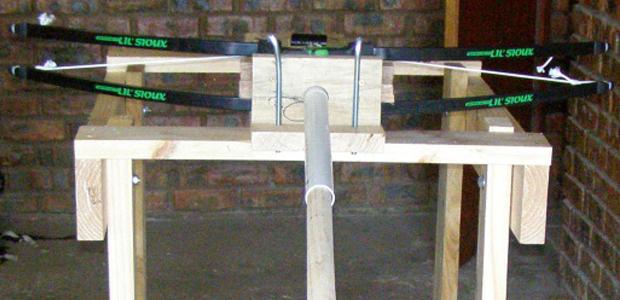

Wilkins would know. As part of this research, her team replicated some of the spear tips using the same materials – the picture of them looks pretty cool – and hafted them to dowels for testing.

That’s because modifications along the sides and at the spear’s tip tell their own story.

In addition to the overall shape of the stone tip – which is very similar to spear tips that were manufactured just 300,000 years ago – damage patterns, known as diagnostic impact fractures, hint at their use.

“Sometimes points are used for other functions,” Wilkins said. “They have a sharp edge, so they could have been used for cutting.”

Using a crossbow that’s been modified for science – researchers like to control things and the crossbow allows them to consistently deliver the same force – the team loaded the experimental spears and then heaved them into a carcass that had already been culled for reasons unrelated to the research.

“Spear tips exhibit way more damage at the tips of the points than along the edges and that’s the pattern we see in the Kathu Pan points,” Wilkins said. Had they been used to cut things, the researchers say their shape would be less symmetrical as one edge’s preferentially sharpened.

It also allows them to control for chips that might have occurred after they were deposited into the fossil record.

“When the piece is in the ground, it gets a white coating on top of it and you can see scars that come off after,” Wilkins said. “We use those as a proxy for post depositional processes because we know those [scars] have nothing to do with use, at all.”

The spear tips were actually unearthed about 30 years ago by Peter Beaumont of the McGregor Museum – he’s responsible for most of the initial excavations in South Africa – but it wasn’t until 2010 that researchers really understood what they were looking at.

“Until quite recently you couldn’t date sites much older than 50,000 years ago,” Michael Chazan, another study co-author and director of the University of Toronto’s Archaeology Centre told SciFare.com.

Using two state-of-the-art techniques, Chazan and a team of researchers from Australia, Israel and France, were able to assign dates to both artifacts found alongside the spear tips and grains of sand in the same layer.

One of the techniques, called U-series/electron spin resonance, looked at the ratio of uranium isotopes in the enamel of animal teeth found alongside the spear tips. The other technique, known as optically stimulated luminescence, essentially measures the radiation that’s trapped in grains of sand.

“We’re putting you in the general ball park, with a high degree of security that we’re in the right ball park,” Chazan said.

In a manuscript from earlier this year, Wilkins and Chazan also dated the layer of soil that’s immediately above the one with all the spear tips – this allows them to say the layer where they were found, is at least as old as the one above it.

“The stratum above it dates to 300,000 years ago,” Wilkins said. “It adds additional chronological control because it gives a minimum age for everything underneath.”

Formally called Kathu Pan 1, the natural processes that led to the site’s creation aren’t clear to researchers – it’s actually a sinkhole – but it does highlight the importance of water to finding evidence of our hominin ancestors.

“People are where water is,” Chazan said. “There’s hominin occupation and animal presence at the site because there’s water.”

The research was published in the journal, Science.

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded