After infecting a group of pigs with a deadly form of Ebola virus, a team of Canadian researchers found they passed it to monkeys housed in cages alongside them – the first experimental evidence of Ebola infection spreading between two different animal species.

Pigs that roam alongside humans may join fruit bats in harbouring and transmitting the Ebola virus.

After infecting a group of them with a deadly form of the pathogen – formally known as Zaire Ebola virus or ZEBOV – a team of Canadian researchers found the swine passed it to monkeys housed in cages alongside them. It’s the first experimental evidence of Ebola infection spreading between two different animal species.

“If it is part of the chain of transmission, it’s a great place where people could help control and prevent the outbreak,” Gary Kobinger, study co-author and Chief of the Special Pathogens Program at Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory, told SciFare.com. “Pigs are easy to see and they’d be easy to vaccinate.”

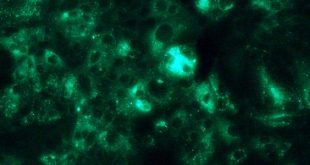

When researchers analyzed how the virus spread to the non-human primates – known formally as macaques – autopsies found the infection in several tissues, including the lungs.

But, when researchers artificially infect non-human primates with the virus – simulating how an infection can occur if it enters through a cut – it doesn’t spread to the lungs.

“If the virus gets directly in their bloodstream, they don’t shed infectious viruses in their mucosa,” Kobinger said. That means the Ebola virus that infected this study’s non-human primates, did so through their airway.

When autopsies were performed on the pigs, the researchers found the virus was largely contained in their lungs. More importantly, they survived the infection and developed antibody defenses to protect against future invaders.

The researchers said the same immune defenses should be present in the domestic and wild pigs where outbreaks have occurred, if they’re blameworthy.

“If we can detect antibodies to Ebola in Africa, where there have been outbreaks in the past few years, that could tell us they are potentially playing a role,” Kobinger said.

The idea that swine could play a role in transmitting the Ebola virus doesn’t necessarily complicate what researchers already know – the finding actually highlights how little they still know.

“It could explain some cases that have no documentation of close contact with bodily fluid,” Kobinger said.

It took 12 days before the virus was detected in two macaques but, the other two were infected in just eight. The researchers say the pattern of infection – the cages were stacked two by two – provided them with their first hint at why.

“We think it’s due to the air flow,” Kobinger said. The first two infected macaques lived in the bottom left and the top right cubicles – directly in the path of a breeze created by the air filtering system.

After being launched out of the pigs’ airway, the researchers say it could have easily taken advantage of the physics, in the same way that a tailwind can enhance a vehicle’s gas mileage or propel a long jump athlete further – an athlete can’t even claim a record if it’s blowing faster than two metres per second.

The researchers say that measuring the size of the ejected material is also important because the pigs were able to transmit the infection, without being in direct contact with the macaques – a 20 centimetre space kept them from coughing or sneezing directly into their mouth and size matters.

“It could be fomites, which are basically large droplets falling on a surface,” Kobinger said. “The non-human primates will touch that surface and then touch their mucosa.”

They could also be smaller droplets called aerosols but, researchers say, that’s likely not the case given what has been observed in the lab and nature – it doesn’t seem to be an efficient strategy.

Other researchers have found pigs pack a mighty wallop when they cough, so restricting the virus to their lungs essentially makes their airway act like an inefficient cannon when they do.

In 2008, a team of researchers from the United States and the Philippines serendipitously discovered a strain of Ebola virus in pigs, after being invited to help investigate a potential string of blue ear disease outbreaks.

Samia Metwally was a veterinarian and virologist on the team invited by the Philippines Department of Agriculture. She told SciFare.com this new research is important because it independently confirms their finding and does it with a second strain of the Ebola virus.

“You really have to question everything around you,” Metwally, who’s currently an Animal Health Officer at the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN, said. “By itself, it’s telling us that we still don’t know much about Ebola virus.”

This matters because the farmers had also developed immune defenses, raising the possibility it could be used to develop a vaccine against the more deadly strains, like ZEBOV – the strain that was experimentally passed to monkeys.

“Using Ebola Reston as a vaccine could be a really good way to control an outbreak,” Metwally said. But, researchers need to understand if those immune defenses target something unique in REBOV – the short name of the virus – or if they’re effective enough to defeat all strains of Ebola virus.

The discovery was serendipitous because the only known reservoir for Ebola virus at the time was fruit bats – a discovery that was also made thanks to some neat technology.

The swine had symptoms of blue ear disease – known scientifically as porcine respiratory and reproductive syndrome virus and the intialism PRRSV – but they found something else, something they couldn’t identify.

So, the researchers created a microchip that stores the signatures to several viruses, called a microarray. When they tested the unknown sample, they found REBOV in the pigs and documented their finding in a 2009 manuscript that was published in the journal, Science.

The latest research was published in the journal, Scientific Reports.

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded