Researchers in the United Kingdom have found a possible relationship between early-life telomere length and lifespan in Zebra Finches – a finding that could have implications for humans.

Researchers in the United Kingdom have found a relationship between early-life telomere length and lifespan in Zebra Finches – a finding that could have implications for humans.

“We found that the telomere length measured at 25 days was the most predictive,” Pat Monaghan, study co-author and Professor of Animal Ecology at the University of Glasgow, told Science-Fare.com.

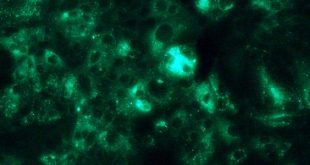

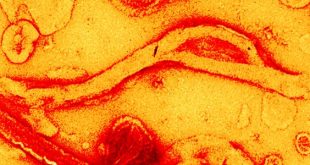

Telomeres are stretches of DNA that flank the ends of a chromosome – like the plastic ends of a shoelace. Every time the cell divides, they get shorter and shorter, so their length’s important for protecting and preserving regions of the chromosome that are necessary for proper cell function. Researchers believe this may be part of the reason human’s age.

“The process of telomere loss and the restriction of cell division is a natural process that takes place in healthy organisms,” Monaghan said. “It has benefits – It prevents cells from unchecked and unlimited growth.”

Studying this process in humans is extremely difficult because of our long lifespan – it’s not easy to study someone continuously from birth to death. Finches have a shorter lifespan, so they can be used as models to predict associations in humans.

“They’re widely kept as pets, so it’s possible to keep them and they can lead healthy lives in captivity,” Monaghan said. “But, they’re not so long-lived that it makes the study go on for decades. The longest lived of our birds lasted almost nine years.”

Although strongest at 25 days, the researchers say they’re able to make accurate predictions up to one year in age.

“We didn’t know 25 days would be the most important, but we did think early in life might be more important than later in life,” Monaghan said. “A lot of [telomere] loss takes place during the early growth phase so we thought that might be particularly important.”

“What we don’t know is if 25 days is important because it’s closer to the inherited telomere length – and maybe that’s what’s most important – or whether it’s indeed environmental factors during that early growth phase that matter,” she added.

Finding a 25 day equivalent in humans, Monaghan says is difficult.

“At 25 days, zebra finches are not quite independent of their parents, but almost. They have done most of their body growth but they still have quite a bit of development to do – so they’re children,” Monaghan said. “They’re not adults and they’re not babies to put it in context.”

Researchers also compared zebra finches that were allowed to reproduce and those who didn’t. They found those who did, experienced a temporary acceleration in telomere loss compared to those who didn’t reproduce.

“And it didn’t matter how much they reproduced – just engaging in reproduction seemed to accelerate telomere loss,” Monaghan said. “Although it accelerated their telomere loss, it looks like it then slowed and didn’t influence overall lifespan.”

“There’s still a lot of variation amongst individuals with similar telomere lengths and how long they live,” Monaghan said. “Telomere length is part of the story, but it’s not the whole story.”

The study was published in the latest issue of the Journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded