A near complete fossil of a new juvenile megalosaur has been unearthed in southern Germany – the most complete predatory fossil ever found in Europe. Extensively covered in feathers and soft tissue, it’s even been declared a cultural object of national importance.

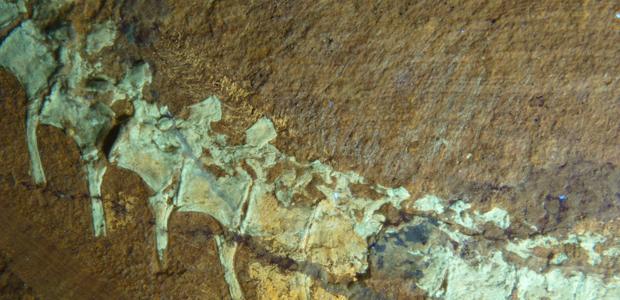

Preserved in limestone that dates back 150-million years, a near complete fossil of a new juvenile megalosaur has been unearthed in southern Germany – the most complete predatory fossil ever found in Europe.

If the image of the Late Jurassic fossil isn’t spectacular enough – it’s even been declared a cultural object of national importance – the team of German and American researchers also found it had preserved soft tissue and that it’s extensively covered in primitive feathers.

“This animal is much more distantly related to birds and yet it still has feathers,” Oliver Rauhut, study co-author and paleontologist at the Bavarian State Collection for Palaeontology and Geology in Munich, told Science-Fare.com.

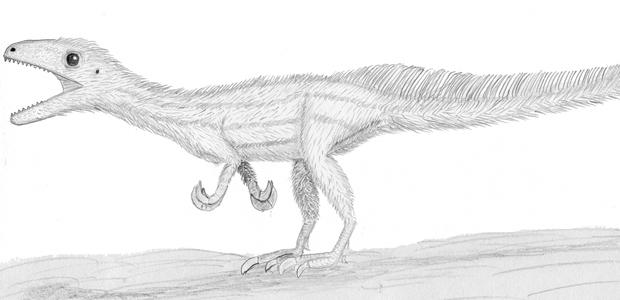

Dubbed Sciurumimus albersdoerferi for its bushy tail, it’s the first feathered dinosaur that’s not a coelurosaur – the dinosaurs that evolved into birds. Megalosaurs, are more closely related to crocodilians and other predatory dinosaurs.

“That indicates feathers were probably much more widely spread among dinosaurs,” Rauhut added.

Brilliantly revealed using ultraviolet light, the simple feathers show up as blue wisps due to their monofilament shape and unique chemical signature. The researchers say they look a bit like hair and may have felt like the down feathers we know on birds today.

“I would imagine these animals, for the most part of their body, to be fluffy like a chick,” Rauhut said.

The hair-like feathers on Sciurumimus aren’t unique either. Similar hair-like structures have been found on other flying dinosaurs.

“If pterosaurs had feathers and these predatory dinosaurs had feathers, that would indicate that feathers are probably the general feature of all dinosaurs,” Rauhut said. “This indicates that probably all dinosaurs – at least as babies – had feathers.”

Preserved alongside the feathers and glowing yellow under UV light are cup-like structures that researchers say may be primitive follicles – the skin organs that grow and anchor feathers – and other types of soft tissue.

“There has been some debate in recent years about whether follicles are primitive for feathers – meaning that if you have feathers, you also have follicles – or whether follicles developed to anchor the large and heavy contour feathers in the skin,” Rauhut said.

Appearing in the skin of such a primitive dinosaur they say, suggests they evolved alongside feathers.

This is hardly a story of primitive feathers and follicles – the beautifully preserved skeleton has also revealed a plethora of its own secrets.

While most other fossils from the same region of the family tree have four claws – even fossils from deeper in the family tree – Sciurumimus has three, starting its own debate.

What’s not as debatable is its label as a juvenile – rather than as a miniature adult species – thanks, of course, to the skeletons wonderful preservation.

“Usually the eyes get relatively smaller, the snout gets longer and you have better ossification of the bony structures,” Rauhut said. The dinosaur was so young, the skull pieces hadn’t even fused together yet – like a baby’s skull has a soft spot until its skull pieces fuse together.

Even Sciurumimus’ teeth tell a story. Standing just 72 centimeters high – about the size of an average one year-old – researchers say it probably had a different diet and lifestyle than adult megalosaurs.

“The teeth this animal has are well suited for hunting small, elusive prey like insects or maybe small lizards,” Rauhut said. “It also implies that these animals were probably not fed by their parents but hunted very rapidly on their own, after hatching.”

Found in the Solnhofen limestone of southern Germany, it was the conditions 150-million years ago, that really allowed for such unique preservation – several other neat fossils have been found there, including this one and the first feathered fossil, Archaeopteryx .

“The limestone’s extremely fine grained and that has the potential to preserve even the most exquisite details,” Rauhut said. The area was also a lagoon that must not have been able to support much life – there’s no evidence the body was disturbed once it landed at the bottom.

“There was nothing that would eat these things or disturb the ground,” Rauhut said. “Basically, everything that reached the ground in these lagoons had the potential to become a spectacular fossil.”

The research was published in the journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded