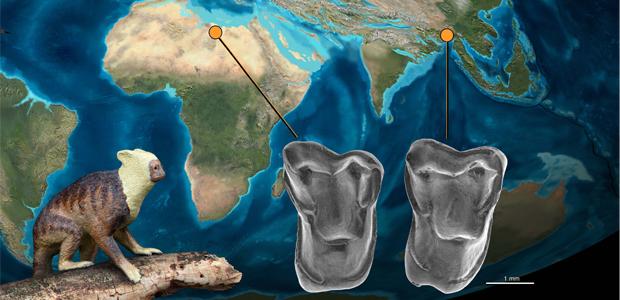

From just four teeth, an international team of researchers have identified a new species of anthropoid primate – the ancestors of humans, apes and monkeys – that’s approximately 37-million years old. Weighing barely 100 grams – about as much as a small stick of butter – Afrasia djijidae may help bridge primate migration from Asia to Africa.

From just four teeth, an international team of researchers have identified a new species of anthropoid primate – the ancestors of humans, apes and monkeys – that’s approximately 37-million years old.

Weighing barely 100 grams – about as much as a small stick of butter – and unearthed at the Pondaung Formations of Myanmar, Afrasia djijidae may help bridge primate migration from Asia to Africa.

“We’ve found nearly the same taxa in both Asia and Africa,” Jean-Jacques Jaeger, study co-author and paleontologist at the University of Poitiers in France, told Science-Fare.com. “That’s a very strong link, considering the huge distance that separates them.”

Sifted from nearly 40-million years of sediment, the teeth – any way you measure them – are just a few millimetres in size – about the same size as a whole peppercorn.

“Most mammalian paleontology relies on teeth because they don’t change through the growing process – they’re always the same size and morphology,” Jaeger said. “They have a very high heritability and their characteristics are, for a majority, inherited from the parents with few variations.”

Given their size, the researchers say Afrasia probably looked much like a tarsier – a similarly sized bunch of primates that live in the jungle of Southeast Asia.

“They’re very well preserved – more preserved than bones,” Jaeger said. “This is why stories of the evolution of mammals are mostly stories of teeth.”

When researchers compared the teeth from Afrasia to those from another anthropoid primate, Afrotarsius libycus – who also lived around the same time, but was unearthed from the sands of the Sahara Desert in Libya – the researchers only found slight changes between them.

These slight changes, researchers say, suggest the immigration to Africa took place during the late Middle Eocene around the same time that primates, like Afrotarsius, first arrived in Africa’s fossil record, approximately 39-million year ago.

“That means there was one peopling from Asia to Africa and recently,” Jaeger said. Had they arrived earlier, the researchers would expect there to be more variation in the shape of their teeth. But, when they compared the sample to older ones from Asia, they found Afrasia’s teeth were more evolved, which suggests it’s a transition creature toward the cradle of humanity, in Africa.

How the primitive primates got to Africa isn’t known. The continent was detached from the rest of Eurasia by the Tethys Sea – the remnants of which became the Mediterranean Sea – but the geography around it changed through time, thanks to both plate tectonics and varying sea levels.

This could have temporarily opened a passage for the many creatures that appear to be showing up in Africa’s fossil record at the same time – two other primitive primates have been found in Libya from about the same time and other rodents are known to have had a presence in both regions.

“How they arrived exactly, we don’t know yet,” Jaeger said. “But, we are sure there was an immigration event that involved more taxa than just anthropoids.”

The idea of exploring the archaeological potential of Myanmar isn’t new. Before the First World War, British Geologists working for the Geological Survey of India – it was part of India before it became Burma and subsequently Myanmar – recovered evidence of anthropoid primates in the region.

“We have found several new anthropoids already,” Jaeger said. The researchers have been visiting the area for nearly two decades, thanks to a special agreement with the government that they renew annually.

Since it may have been one of the transition creatures that journeyed to Africa from Asia, researchers named the new anthropoid primate, Afrasia. The latter portion of its name, djijidae, pays respect to a young girl from Mogaung village, in central Myanmar.

The research was published in the journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded