A small fish found in the pterosaur’s throat may be what led to the deadly – and surprisingly common – encounter between the flying dinosaur and the predator fish.

Immortalized in the fossil record is the unusual portrait of a long-tailed pterosaur – known as Rhamphorhynchus – alongside the mouth of a large ganoid fish called Aspidorhynchus.

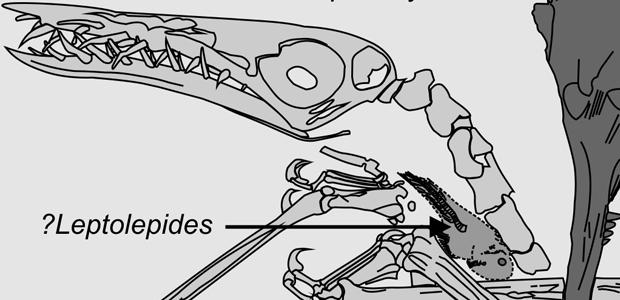

After recovering five of these fascinating fossils – which is a staggering amount for such a rare type of interaction – researchers from Germany have found a small fish preserved in the throat of one pterosaur.

A common prey item for both hunters – and common in the fossil record – researchers say the leptolepidid fish may explain what led to the deadly encounter approximately 150-million years ago.

“Normally this pterosaurs’s not part of the prey of Aspidorhynchus because it’s too big,” Eberhard Frey, the study’s co-author told Science-Fare.com. “Apparently it grabbed the pterosaur and dragged it underwater before Aspidorhynchus recognized the mistake it made.”

Because the pterosaur wasn’t able to breathe underwater, it would have drowned fairly quickly – dragging Aspidorhynchus down as it sunk.

It didn’t die without putting up a fight first though – check out how mangled the left wing in its mouth is, compared to the free one.

“[It] failed to shake it off because the wing membrane got tangled in the teeth of the fish,” Frey, who’s also a biologist at the National Museum of Natural History in Karlsruhe, said. “It became an obstacle for the fish and it needed to get rid of the pterosaur, so it started to shake and shake.”

Previous research has shown the complex muscle tissues making up Rhamphorhynchus’s wings were fibrous – like the meat that gets stuck between your teeth after chewing it – and were much more robust than tissue found in modern day bat wings.

“These fibrils consist of very tough and dense connective tissue that’s like chewing on a very, very tendinous piece of meat,” Frey said. “These fibres were so tough that they couldn’t be ripped during shaking so the membrane remained viable until the pterosaur and the fish died.”

Near the bottom of the sea, low oxygen levels would have then suffocated the Aspidorhynchus.

Given the position of the leptolepidid fish in the pterosaur’s esophagus – it’s so preserved they can even see its fin details – the researchers say the animal wasn’t regurgitated, meaning the deadly interaction occurred almost immediately after the Rhamphorhynchus’ successful hunt.

“We don’t know if the fish were alive or dead and floating on the water’s surface though,” Frey said. “We only have evidence that these fish were swallowed.”

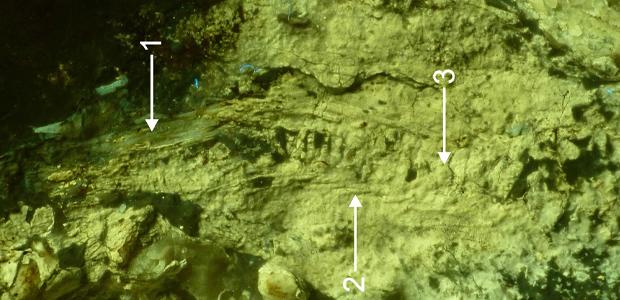

Fine details – including those of the stomach contents – were revealed using ultra violet light. Under UV light, they found partially digested fish – some of which would be alongside the one found in the pterosaur’s throat if it had been regurgitated, the researchers say.

As you can see in the pictures, UV light interacts with the specimen uniquely – allowing researchers to see things that otherwise go undetected in normal conditions.

The stomach contents also help us understand what the pterosaur ate. Not much is known about it and much of what they know is based on mechanical restrictions imposed by the pterosaur’s skeleton.

Limited by its biology, the pterosaur had to practically skim the water’s surface in order pluck the fish from it.

“Because of its short neck, the pterosaur had to go down very low to the water’s surface – maybe just five or six centimetres above,” Frey said “By doing this, the pterosaur had to pierce the water’s surface – and probably accidently touched the water’s surface with its wing tips – as do some seagulls today.”

“That attracted a fish that hunted the same prey, at the same time and in the same place,” he added.

The same biomechanical principles are what led researchers to believe this was a chance encounter, rather than an attempt to hunt the pterosaur too – Aspidorhynchus couldn’t open its mouth to swallow a prey that was as big as it was.

The sample was hauled out of the Solnhofen Limestone in Southern Germany. The area’s belched several extremely complete fossils, including some of the most complete flying dinosaur fossils – and all of the major players in this one fossil.

In addition to this encounter, three other nearly complete tableaus have been unearthed and a fourth specimen shows a pterosaur wing in the Aspidorhynchus’ mouth. This fifth specimen is the first to show the pterosaur was alive immediately before it got caught up with the other predator fish.

This gem of a discovery was published in the journal, PLoS One.

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded