Using images snapped by NASA’s Terra satellite, researchers from Harvard and MIT have mapped more than 14,000 archaeological settlements across northeastern Syria.

Using images snapped by NASA’s Terra satellite, researchers from Harvard and MIT have mapped more than 14,000 archaeological settlements across northeastern Mesopotamia.

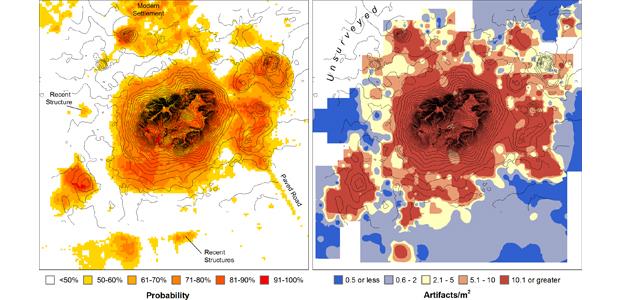

Resolved using Terra’s ASTER sensor, the images reveal an extensive network of rural landscapes, travel corridors and city settlements, spread across 23,000 square kilometres – an area about the size of New Jersey – in what’s now known as northeastern Syria .

“These rural settlements are extremely important,” Jason Ur, study co-author and anthropological archaeologist at Harvard University told Science-Fare.com. “These are the producers that sustained the populations that lived in those big cities.

“Here we have an opportunity to put these producers back on the map, which is something we owe them,” he added.

The researchers trained the sensor to detect changes in soil related to human settlement.

Known as anthrosol, it’s a soil that’s lighter in colour and finer than soil that hasn’t been settled. Because it’s so rich in organic matter, it can be easily detected from space.

Another feature researchers can measure from space is mounding – thanks to research conducted by NASA’s global Shuttle Radar Topography mission – SRTM – model.

With 8,000 years of civilization, researchers can actually find areas of land that are elevated because cities have literally been rebuilt on top of themselves.

“They’re basically piles of collapsed mud brick,” Ur said. The mounds – known as Tells in Arabic – are impressively massive and researchers say seven out of every ten were significantly large enough to be detected from space.

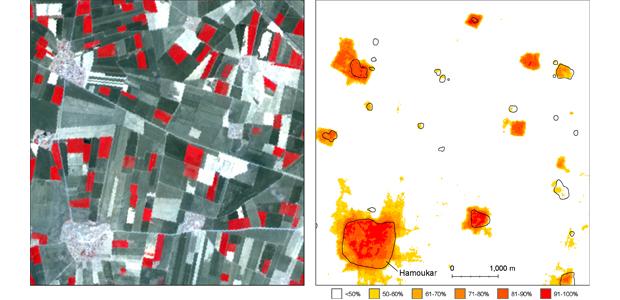

They then compared those images to more simple and salacious ones – declassified images from the Corona spy satellite program. Ur’s first started studying the images, about a decade ago.

“It’s very helpful for me to take the potential sites identified by our multispectral analysis and then see what they look like on the Corona images,” Ur said. ASTER doesn’t just take pictures, it images across the spectrum – even outside the visible portion – allowing it to key in on details that aren’t as easy to spot in visible light.

Mapping such an expansive area allows researchers to look at potential patterns associated with long term settlement.

When they compared several settlement factors, like total number of sites, along with the total and average volume of the sites, they found a strong association to available water – and, like in nature, they found deviants, including Tell Brak.

“[It’s] both far away from water courses and in an area of dry rainfall, yet it’s the largest archaeological site in the area,” Ur said. “This is fascinating because here, it’s clear that pure environmental reasons for settlement don’t apply.”

“This is a place that had some cultural meaning that we can only guess at,” he added.

The social unrest that’s gripped Syria for the last year has virtually ended all opportunity to do field work there, safely.

However, across the eastern border of Iraq, in the Kurdistan Region, archaeologists are beginning to return and study the portion of Mesopotamia that‘s been systematically ignored for the last decade – and under the previous regime.

“We know almost nothing about broader landscape patterns of settlement and urbanism there,” Ur said. “There’s really a lot to be learned.”

The researchers say these techniques could also help us learn more about and target efficiently, other archaeological sites of interest.

“There’s no reason why these methods can’t be expanded and applied to anywhere else in the world, under similar conditions – broad, agriculturally productive, alluvial plains,” Ur said. “That kind of environment describes the heartlands of most of the world’s early states and empires.”

The Terra satellite could be the hardest working satellite in space. Truly a global research project, it conducts research on topics that range from archaeology, to volcanology.

Launched in 1999, it has four other onboard sensors that help measure Earth’s atmosphere, lands, oceans and the radiation that bombards it.

The research was published in the journal, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded

Science Fare Media Science News – Upgraded